I had such high expectations for this book and was left with very mixed feelings.

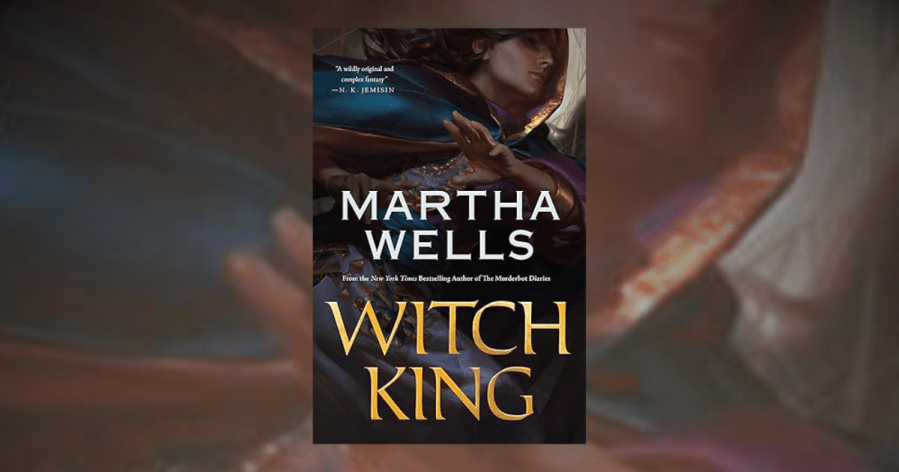

This was the first book by Martha Wells that I’ve read, but I saw that Witch King had received some great reviews and solid recognition (it won the 2022 Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel and was a nominee for the Hugo Award and Nebula Award), so it went to the top of my TBR.

Witch King is a complex and richly detailed story, with a cast of intriguing characters and one of the most unique worldbuilding and magic systems that I’ve encountered recently.

However, despite these promising ingredients, the pacing was weighed down by an ambitious (and unnecessary) dual timeline narrative, and an obscure delivery of important plot elements that ultimately made the story somewhat tedious to read.

[WARNING: This content contains spoilers]

The story follows Kai or Kaiesterron, the demon prince or “Witch King,” as he tries to figure out who killed his last host body and imprisoned him in a stasis-like sleep for over a year, with the help of Ziede the witch, and a street child named Sanja.

The story alternates between the Present and about sixty years in the Past, when Kai helped a mortal prince stage a coup against a conquering warlike culture known as the Hierarchs who destroyed half the world and imprisoned demons using their ability to draw magic from a mysterious source known as the Well of Power.

Twice the Timeline. Half the Momentum

Wells uses a dual timeline structure, alternating between the Present (Kai and company figuring out the conspiracy of who trapped him and why) and the Past (helping stage the coup).

This is a recurring problematic trend I’ve noticed in newer fantasy.

Authors are dreaming up big worlds and epic adventures that sweep across vast periods of time and feature huge character casts – so they split up the book, using strategies like dual timelines or multiple character POVs to try to cram it all in.

And often, it just isn’t necessary.

There is a time and place for these structures, but in too many cases I think they’re used because the author feels overwhelmed by the scope of the plot and backstory, and defaults to thinking “it’s all important, I can’t leave anything out!”

In Witch King, the dual timeline created an additional complicated layer to an already dense plot. Rather than being able to enjoy the story and characters, I had to keep remembering who was who, and what they were doing, and it slowed the pace to a crawl.

Writers must remember to bring balance to their story. You will spend days, months, even years learning your world and characters, but your readers will have hours. If they are constantly flipping back and forth between chapters and consulting the character list, it means the story is too complex and not in a good way. It shows that the author did not take the time or employ the right strategies to make the story enjoyable and balanced.

With that, here are some other options that would have added lightness and movement to the pacing and given Wells more time to focus on character development and explore the other fascinating aspects of her world.

Alternative strategies to a dual timeline:

- Flashbacks: Some of Kai’s memories are foggy when he comes out of his stasis. During the Present Day, we could have seen flashbacks of his Distant Past, perhaps in strange dreams or fragmented memories when he sees/touches/tastes/hears something that jars his memory. Readers often don’t need the full backstory and only giving them small glimpses at a time into the past can create a sense of legend and suspense as the mystery unfolds.

- Interactions with characters from his past: Kai could run into more characters along the way that help the readers piece together what happened. I feel like Wells set up that plot device with a few characters including Ramad (an interested historian ready to record and learn Kai’s history) but then Kai ended up not sharing very much at all.

- Explaining things to new characters: Again, this was perfectly set up with the curious street urchin Sanja, Kai and Ziede could have taken more turns filling in the kid about how things used to be in small doses.

- Finding Primary Source Material: Ramad could have brought along an old journal or archival material he found that documented the revolution, and during their little history exchange conversations, he could have fact checked things with Kai.

- Keep the Past scenes short and distinct: Or, if we stick with the dual timeline narrative structure as is, it might have helped to have had shorter “Past” chapters. Or made them more distinct by telling them through someone else’s POV. But in this case, I still think this story would have been stronger with one of the above strategies because it was already complex enough through its naming structure, political/historical background, and magic system.

- Or just give in and write Book 1 about the origin story: That is also an option! Look at Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. We start in the Present, and then the first two books are basically a huge flashback as Kvothe recounts his story. There are tiny interludes along the way where we jump back to the present. Kai’s legacy is such that perhaps something like this structure would have served the story better.

If you are going to use dual timelines, ask yourself if there is really enough of a plot in both story arcs for it to hold up on its own, or if you are doing it because you love the backstory you created and don’t want to cut anything out. In Weyward, I actually think using multiple timelines was a great fit (although I had other issues with the POV and tense choices).

There’s one final strategy that could have been used instead of, or in addition to, a dual timeline, and that is sneaking in some pure, undisguised narrative summary.

What is narrative summary?

Narrative summary was more common in older novels. It was when a story would have big paragraphs or even chapters of the narrator simply telling the reader the backstory – who the people were, how they knew each other, the history of the culture or the setting, etc. Read the first couple chapters of Grapes of Wrath and you’ll know what I mean.

I’ve often wondered if fantasy authors don’t use this this more is because they’re worried it is “telling,” instead of “showing,” and that is really too bad because it can be a very useful device for complex narratives when used right.

That being said, too much narrative summary at once can be dull to read, and writing styles have changed, so narrative summary as it once looked has gone out of style.

We still use it of course, and I see it disguised in fantasy quite a bit, usually hidden among dialogue between two characters.

It’s the whole, “Tell me what you know of the history of [fill in the blank], young one,” (see the first fifty pages of Sword of Shanarra, or towards the end of ACOTAR when a servant relates pages upon pages of backstory to Feyre before she goes Under the Mountain). Or it can show up as a family member revealing someone’s true past, or an antagonist monologuing about why they did what they did. I think these strategies all work, but they can still come off as info dumping, so use it judiciously.

Another reason to use a bit of narrative summary now and then is that “showing” takes longer, and it can slow down a complex story and end up being more confusing than mysterious.

For example, in the Witch King, Wells hints at what the “Well of Power” is for three hundred pages, but we don’t actually get what it is or does until close to the end. That isn’t necessarily a problem on its own, but nothing in this book is explained. If everything about the world has to be inferred, it can get tedious.

Here is an example of adding in a tiny bit of narrative summary from the first chapter of Sabriel, from Garth Nix’s Old Kingdom series:

“Magic only worked in those regions of Ancelstierre close to the Wall which marked the border with the Old Kingdom. Far away, it was considered to be quite beyond the pale, if it existed at all, and persons of repute did not mention it. Wyverley College was only forty miles from the Wall, had a good all-round reputation, and taught Magic to those students who could obtain special permission from their parents.”

Throughout the series Nix definitely goes on to show the difference between Ancelstierre and the Old Kingdom, but giving a dash of context right from the beginning helps the readers orient themselves to the story.

Final Thoughts

I think Wells is an excellent writer and created a very unique world. But the Witch King was hindered from dense worldbuilding that was not paired with the right narrative structure to make it an enjoyable, well-paced read.

By using some of alternative strategies to a dual timeline, Wells could have kept the momentum going in the Present plot and given more space for the incredibly interesting worldbuilding elements she created. I wanted to learn more about the heart pearls, the Hierarchs, the magic system, the relationships, the gender fluid, soul-eating, morally neutral demons . . . but everything felt very surface level because there was too much plot.

That being said, this is book one of a series and it is no small task to set up such an ambitious story so I will check out book two to see if she is able to give her world and characters more breathing room.

What did you think of the Witch King and the dual timeline?

What are some books that use dual timelines well?

If you’re writing a story with complex worldbuilding and a big backstory, what strategies are you using to keep the story balanced and enjoyable for the reader?